Teaching Fearless

The 2018 Washington State Teacher of the Year's Journey toward Hope

Serbia Day 2 – Šid

My first impressions of Serbia were that I had landed in a nation who, learning from their history, is committed to being open and welcoming. My second day confirmed those impressions. I had the pleasure of visiting the small town of Šid on the boarder of Croatia. The reason for this visit was to tour a reception center, which houses migrant families heading north to find permanent homes and to visit local schools who have worked to welcome migrant children into their schools.

One of the most profound aspects of Serbia’s inclusion of migrant children into their schools is the fact that the majority of migrants who come to Serbia are not seeking to stay there, but rather are passing through to different destinations. Many nations would choose to simply process, house, and send away people not seeking asylum in their nation. Serbia is different. They follow closely the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Serbia values all humans and recognizes the right of children on the move to a quality and consistent education. This is a unique and honorable stance.

Our day started at Sava Šumanović Secondary School, a local high school who has worked to include their migrant community members into their school. There I met with Jovan Komlenac, the school psychologist, who also teaches classes and the school’s director, Nada Hromiš Aničić. I learned so much about the intentional process and steps they went through to begin inclusion of migrant children into their classrooms.

Jovan’s compassion and clear commitment to the education of every student in his community immediately struck me. His passion is an obvious catalyst for his school and colleagues. They started their work toward inclusion two years ago, when they connected the children in the migrant center to students in their school to complete projects together and to have migrant families share their stories. They then began to make visits to the migrant center as a community — educators, students, and their parents. With exposure and shared experiences, prejudices immediately broke down and they were then able to begin including migrant students into their classrooms, with the support of all teachers and parents.

Jovan’s compassion and clear commitment to the education of every student in his community immediately struck me. His passion is an obvious catalyst for his school and colleagues. They started their work toward inclusion two years ago, when they connected the children in the migrant center to students in their school to complete projects together and to have migrant families share their stories. They then began to make visits to the migrant center as a community — educators, students, and their parents. With exposure and shared experiences, prejudices immediately broke down and they were then able to begin including migrant students into their classrooms, with the support of all teachers and parents.

Specifically, Jovan explained that they follow these tenets: 1. Everyone must feel safe. 2. Social inclusion is key in order to ensure all students have a sense of belonging at school. 3. Learning content comes only after achieving the first two tenets. They also implemented a very detailed plan to ensure everyone was on board and prepared to welcome their newest community members.

First, school staff and students visited the camp to build a bridge between the school and the migrant families. Second, Jovan did a professional development training with the school staff called, “Suitcase” (You have to leave your home in five minutes, pack a single suitcase, what would you take?) to build empathy and to open them up to the experiences of the migrant students and their families, as well as to build skills to meet the needs of the newcomers. Third, they organized a welcome day for the new students and their families. Fourth, they not only prepared the migrant families, but also the Serbian families, in order to allay fears and build connections. Finally, they included all newcomer students regardless of previous education or length of intended stay in Serbia.

Since beginning inclusion two years ago, they have successfully opened up their classrooms to all migrant children at the Šid reception center. This, alone, is impressive, especially considering the transience of the migrant community they serve. Whether a family is there 3 weeks or 3 years, every effort is made to welcome them and include them in their schools. They use peer-to-peer classroom support, and teachers are intentional in how they create comprehensible input for newcomer students. They work to ensure the same level of academic rigor for all students, but with different entry points. They are still working through this process, but every student benefits from their efforts. I saw this clearly in the classrooms I visited.

I ended my visit to Šid with a tour of the migrant family reception center. The facilities are wanting. There are limited resources and housing is difficult to maintain, with a constantly fluctuating population of migrants. The rooms are far from ideal, with families sleeping 6 to a room, sometimes more. However, they get to keep all of their belongings with them, as each room has storage shelves. The gates to the center are kept unlocked and families are free to come and go as they please, as long as they sign in and out. They are welcome in the greater Šid community. I was there during Ramadan and the center kitchen facilities and cafeteria operated with respect to the needs of the Muslim families they served.

That visit offered me a new glimpse into the migrant experience. An Afghani family shared with me their difficulties moving through the various nations after fleeing persecution in Afghanistan. They were thankful for how they were now treated at the migrant family reception center in Šid, especially because they have a special needs son. They hope to move to Germany where they have a family member waiting for them. It has not been easy, but they say this reception center has been one of the best so far. They’re not sure how long they will stay.

What I saw and experienced in Šid gives me hope. Hope because the individual people in a community make a difference. It is the willingness of the residents, particularly those within the schools, who make life bearable for migrant families. Who welcome them and work to ensure they know they belong, even if these families aren’t planning on staying. This is a lesson for all of us. When we are open and welcoming we all benefit.

Serbia and Being Welcoming – Day 1

Serbia is beautiful. It’s a small Slavic country with a rich and complicated history that has taken them to where they are now — open, welcoming, and always working to be better. I’ve been looking forward to this trip for six months. Now that I am finally here, with my feet planted firmly on Serbian soil, it is so much more than I could’ve imagined.

Serbia is beautiful. It’s a small Slavic country with a rich and complicated history that has taken them to where they are now — open, welcoming, and always working to be better. I’ve been looking forward to this trip for six months. Now that I am finally here, with my feet planted firmly on Serbian soil, it is so much more than I could’ve imagined.

The first thing I witnessed was the deep compassion Serbians have for one another. As my airplane-mates and I waited for our luggage, there was a terrible tumbling sound coming from the escalator. An elderly gentleman lost his footing and fell, head-over-heels, down the moving steps. Several Serbians dropped their own baggage, phones, glasses, to run and help the man up. They then escorted him to a seat, his head bleeding, and waited with him until his family could be located (they were waiting for him outside of customs), and the medics came. It is rare today to see so many people jump to another’s aid in our communities. While scary, the moment — the compassion and the community — washed over me and I knew I would learn so much on this short, five day trip.

My host, Milan Dakić, the Deputy Ombudsman in charge of Children’s Rights, picked me up and we started the hour-long journey from the airport to Novi Sad. He told me of the history of his nation, and the many languages spoken in his city. As he spoke, I had the pleasure of taking in the beauty along the motorway.

Once in Novi Sad, after dropping my things at the hotel, Hotel Veliki, an inviting and comfortable hotel near the town center, we went walking through the city in search of lunch. The streets here are narrow and there are cars, but few. The streets were lined with cafes and shops and packed with people on this warm, clear Sunday.

The thing that struck me immediately was the various people about. There were children in groups, teenagers lounging in the park and at the cafès, middle-aged folks eating, and older community members sitting together on benches. Everyone was out, enjoying the weather and taking advantage of this beautiful Sunday to be together. I didn’t see a single phone. I saw people chatting and enjoying one another’s company. I saw generations sharing the same space. I saw families, and couples with dogs. I saw joy and happiness. I saw connection.

Milan and I enjoyed a leisurely lunch then I returned to the hotel for a rest after my long journey from Spokane to Belgrade. I then had the pleasure of meeting the city Ombudsman, Zoran Paclović, and Milan’s wife, Daniela, for a drink and wonderful conversation about migrations and how to best meet the needs of our immigrant children and their families in our communities.

Today was the start of so much learning. I can already tell Serbia is an example for all of us. I can’t wait to share all of it with you.

The Kids Aren’t All the Same

I can rely on one thing every time I visit a school, whether it’s here in Washington state, or in San Francisco, California, or in West Texas — consistency. In every school and every classroom, I always feel at home.

Most schools look and feel the same, no matter where they are located on the map . I can always count on decorated hallways with motivational messages and student work. The classrooms have a similar look and feel, desks and whiteboards, literature-rich walls, a teacher’s workspace, and books, so many books. It’s comforting.

We all know what to expect when we walk into a school, no matter the community. For me, this is both comforting and concerning. I am comforted because I always know someone will greet me when I walk in. I know there will be energetic teachers at the front of classrooms. I know that students will be hard at work or avoiding work at their desks and I can always hear laughter on the playground at elementary schools.

It is concerning, because we appear to have a very specific idea of school and this idea is the same in almost every community. Yet, just like in our classrooms, where we always have new students each year, no two communities are the same. Each one needs something different, yet the traditional layout of our schools suggests we don’t seem to be responding to those needs.

Recently, I visited the small town of Marfa, Texas. The school district is quite small, with fewer than 500 kids in their system. Just as in school visits past, as I entered the school I was greeted by a stern, but kind office manager. Kids bustled through the hallways with their backpacks slung across one shoulder, and the hallway was lined with classrooms, doors open, desks in lines or semicircles, and lessons scrawled across whiteboards. The hallways were warm and inviting, plastered with posters and inspiring quotes. All of it familiar, and comforting.

An administrator toured me through the school bringing me into an 8th grade English class and then over to a 9th grade math class. The district was small enough to house the middle and high schools in the same building. In the math class, I spoke with several students and the teacher. I spent only a few minutes talking with each student, but in that short time I learned one had just moved there from Austin, another wanted to be a nurse and was working on graduating a year early, and yet another dreamed of coding, but wasn’t sure he was college material. The teacher had only been at the school for a couple of years. He’d come here from Arizona, where he’d taught in a bilingual program. There were only eight students in the class.

More than 75% of the student-body identifies as Latinx and/or Hispanic. Every student I spoke with was bilingual, not only could they speak Spanish, but were also literate in Spanish. Additionally many of the educators I spoke with were also bilingual. Yet, at this school, students did not have access to dual language or bilingual instruction. Additionally, this small math class of only eight students was taught in exactly the same way as one with 30 students. In each of the classes I observed, I saw teachers lecturing up front and students sitting in desks in rows, taking notes, and engaging via discussion.

I see this standardization or traditional delivery of instruction everywhere. I have seen some variations. Amy T. Andersen’s classroom in Ocean City, New Jersey is one. She has adjusted her seating for deaf culture. Students sit in an arc around the room to ensure they can all see one another. Amy’s been able to adjust her instruction to better meet the needs of her students and to provide an authentic experience for them. I’ve also seen flexible seating, with tall tables, short coffee tables, couches, bean bag chairs, and traditional desks mixed in. Although, flexible seating is only one strategy and must be accompanied by additional innovation in instruction to truly make it flexible.

What it comes down to is that it’s not about mandating or standardizing instruction. It’s about giving schools the flexibility to meet the needs of the community in which they reside. In Marfa, Texas that could mean implementing dual-language without having to jump through impossible hoops to do so. Or, exploring new modes of teaching and assessment because their small class sizes allow for options. For example, teachers could focus on mastery rather than level, allowing students to work at their individual competency and pace, maybe a form of flipping their classrooms in order to provide more one-to-one support.

The point is, schools need to meet the direct needs of their communities. Sometimes this means we shouldn’t all look and operate the same, no matter how comforting that feels. We must look critically at our communities and try something new. It’s challenging, but it’s the right thing to do.

*Check out what these educators have to say.

A Good Start: Representation, Connections, and Mattering

I was gifted the opportunity to read Dr. Bettina Love’s forthcoming book, We Want to do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom, to be released in Feb. 2019. In the book, Dr. Love, an associate professor of Educational Theory & Practice at the University of Georgia, discusses the importance of “mattering”—specifically that it is not enough to simply make it through the day: students, especially those of color, must feel that they matter. Mattering means students are represented, are seen and heard, and know they belong in school. Students are not simply there to learn, but to believe in their potential and have the opportunity for success beyond high school. They have the right not simply to survive, but to thrive.

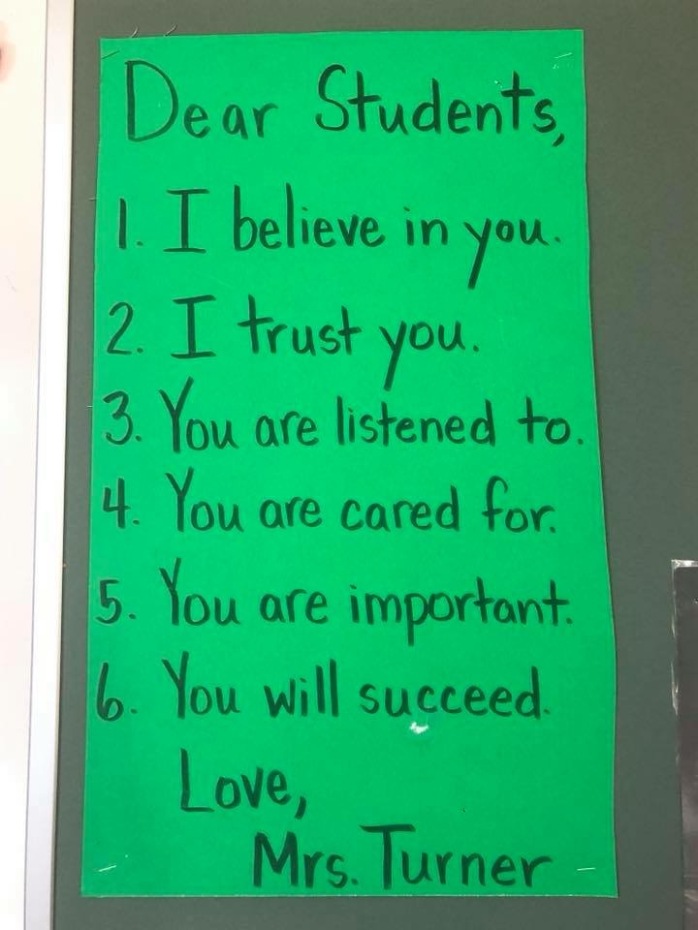

I use this phrase a lot when speaking about serving students: “we must show students they matter.” Dr. Love’s book helped me to explore this phrase. What does it look like to show students they matter? How do we articulate this from the first day of class and believe it’s true? The answer, for me, is intentionally being culturally responsive, both in and outside of the classroom

I love the the start of a new school year, when the school is bustling as we all prepare for the year ahead. One of my favorite activities is a visit to the store for school supplies — pens, pencils, paper, notebooks, and, of course, decorations. We all want to set the right tone, to ensure our classrooms are inviting, comfortable, and engaging. One piece we often miss, however, is leaving room for student representation and voice. It’s disconcerting to have a blank wall, especially when we have our own ideas about how our classrooms will run. It can be difficult to hand some of that authority over to our students.

Being culturally responsive is more than hanging motivational posters or world flags around the room, it is an open willingness to accept students as they come to us, and a commitment to seek to know our students as both learners and as valuable, beautiful human beings. This means we acknowledge our students come from a variety of backgrounds that can create challenges, but that we also recognize the strengths and uniqueness those backgrounds provide. We should view students through their assets and build from there.

As we close out the start of the school year, here are three suggestions for teachers to take on this year’s journey:

- Begin with Yourself: Every interaction in our classrooms starts with us. Self-reflection and self-knowledge are essential to understanding how our experiences in life have shaped our perceptions and contributed to our biases. Our perceptions and biases deeply impact our connections with our students. If we understand where we come from, our social groups (race, ethnicity, gender identity, religious affiliation, socio-economic status, etc.), we can then recognize specifically how we differ from and are similar to our students. We can check ourselves, work to set aside our biases, and be open to all of our students— better able to see the assets and gifts they bring with them into our classrooms. I, personally, do this difficult work of self-reflection every day.

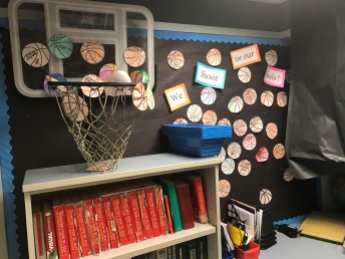

Picture courtesy of Wendy Madigan Turner, 2nd Grade Teacher at Mount Pleasant Elementary

- Be Interested in Your Students: We all know our primary focus is our students. But sometimes we can get caught up in our curriculums or making it from point A to point B, and forget that connections are what truly count in our classrooms. The more connected we are with our students and they are with one another, the more confident they are and the more growth they show. At the beginning of every semester build strong relationships with your students. Get to know them both as learners and as individuals. This also means taking time at the start of the year to build community in your classroom through specific activities aimed at helping everyone get to know each other and setting up a structure for weekly class meetings.

I It also means reaching out to families. I often drive through my students’ neighborhoods. I set up meetings with students’ families and visit their homes. I learn so much about my students from seeing their life outside of school and visiting with their families. If possible, find out who is in your class before the start of the school year and learn something positive, a strength or talent, before you even meet them.

- Leave Room for Student Expression: There are so many awesome products out there for our classrooms- and so many pictures of the perfect classroom—colorful and inviting, engaging and dynamic. It’s tempting to want to replicate these environments without personalizing them based on your students. Resist. Every classroom is different and every new group of students is unique and requires their own environment. Student voice is essential to that environment. While it can be a bit disconcerting and challenging to our sense of control as educators, leave at least one wall blank and give your students opportunities to fill it up, not simply with their work, but with their ideas, their cultures, and their personalities. In my context, students develop classroom expectations, they make posters about themselves and throughout the semester they post representations of who they are and where they come from. I learn from them and they learn about one another. It’s a way to build community.

Picture courtesy of Wendy Madigan Turner, 2nd Grade Teacher at Mount Pleasant Elementary

As Dr. Bettina Love reminds us, students, especially students of color, need to know they matter. One of the biggest reasons students leave school is because they do not feel represented or welcome in their schools. They don’t believe they belong. We must be culturally responsive. First, we must seek to understand ourselves in order to be open to every student who walks through our doors. Second, we must connect with students and really know them. Finally, we have to relinquish some control to our students and give them agency in our classrooms. Empower every student to assert their voice. Show them they matter.

*This is only the tip of the iceberg – cultural responsiveness is not easy, it’s not a checklist, it’s a commitment and there are no quick answers – there is always more work to do…

Impact vs Intent: “I’m sorry”

The evening before the National Teacher of the Year announcement on CBS, I travelled to New York City by train. A friend and I boarded and chose seats in the second to last car. It was a commuter train that ran several times a day. This was during rush hour, so the train was expected to be full. Several times, the conductor announced over the loudspeaker that we should ensure all seats were available at each stop so that people could sit. Of course, none of us listened.

The evening before the National Teacher of the Year announcement on CBS, I travelled to New York City by train. A friend and I boarded and chose seats in the second to last car. It was a commuter train that ran several times a day. This was during rush hour, so the train was expected to be full. Several times, the conductor announced over the loudspeaker that we should ensure all seats were available at each stop so that people could sit. Of course, none of us listened.

Most of us pulled out our laptops to get some work done during the journey and virtually every person on the train had their backpacks or briefcases sitting on the empty seats next to them, including me. After the train departed, the conductor came through and checked everyone’s tickets, but never mentioned the bags on each of the seats.

At the next stop, two women got on and sat in the seats across the aisle from my friend and me. They, too, placed their bags on the empty seats next to them. Again, none of us placed our extra baggage in the overhead bin, despite the repeated instructions on the loudspeaker.

This time, when the conductor came through the car to check tickets, he stopped at the two women and told them to remove their bags from the extra seats and put them in the overhead bin. He did not ask anyone else to do the same. What was only difference between the rest of the people in our car and these two women? They were black.

Both women expressed displeasure with being called out when none of the other passengers were asked to remove their bags. As an observer, it appeared to be a clear case of discrimination based on race—something the women voiced, as well. The reaction of the conductor further confirmed this assertion, as he refused to address his bias. Throughout the next couple of stops, each time the conductor would come through the car, one of the women would explain again his display of discrimination and ask for his name. Each time, he would get more visibly upset and would refuse, avoiding eye contact and grumbling under his breath, his emotions clearly escalating. After a couple passes through, others of us began to request his name as well, supporting the women, as the conductor had clearly been wrong in his actions.

Finally, after several passes through the car he stopped. We noticed his nametag turned toward his stomach so none of us could see it. He said, “If you are going to take my name, I need your names, too.” We all questioned his behavior and asked why he would need their names, but he would respond to none of us. He forced the women to give him their names, copying the names from their tickets, while still refusing to give his own name, then he stormed off out of the car.

When he returned the final time, he brought a police officer. The women began to explain what happened, and without listening to them, the officer asked them to go with him. That’s when I increased my involvement. I raised my hands and asked the officer to please hold on—that there was no need for the women to go with him because the conductor was the person at fault in this situation and who had also escalated it. The officer reiterated that the conductor had made several announcements concerning placing bags in the overhead bin and passengers were expected to comply. I motioned to my own backpack and explained that the problem was not in the rule, but in the conductor calling out only these two women, who also happened to be the only people of color in the train car. If the conductor had been serious about the rule, he would have instructed all of us to put our bags away, but he did not. The women then took the conductor’s name, finally. The police officer reiterated the rule and left without further incident.

This unfortunate situation escalated, not because of the women calling out the conductor’s blatant racism, but because he refused to recognize the impact of his actions. At the end of the encounter, the conductor did mumble under his breath that his intention was not to discriminate. It fell far short of an apology, and he did not return to our car for the rest of the trip.

This is a problem. Regardless of our intention in our words and actions, it is the impact that matters. If something we do or say negatively impacts another person or group of people, it doesn’t matter what we intended. It is our responsibility to recognize our impact and to apologize.

If the conductor had simply said, “I’m sorry.” If he’d recognized how his actions could have been interpreted as discriminatory based on the women’s race and apologized, the situation would not have escalated at all. It’s possible the women would not have wanted to take his name to report his behavior. Instead, he dug his heels in and refused to reflect on his own behavior.

So many situations like this one happen every day. It doesn’t take much searching to find countless stories of implicit or explicit bias, like the Starbucks incidents. These situations escalated not because of the victims calling out the racism, but because of the white people perpetrating the racism who do not recognize the impact of their actions and, who frequently, double-down by calling the police.

All of us act in discriminatory ways. It’s an unfortunate and inevitable part of human nature. Instead of reacting defensively and denying the action, challenge yourself to recognize it. Recognize the impact on the other person or persons and apologize. It’s that simple.

If you don’t like being called a racist. Don’t be racist. When you mess up and discriminate, just say you’re sorry and be more cognizant next time. Learn from your mistakes.

Recognize your impact regardless of your intent. Say, “I’m sorry,” mean it, and be better. It’s that simple.

The Poverty Next Door…

Jenny Tenney, the ESD 105 Regional Teacher of the Year, took the day off from school to show me her school district – White Swan. We met in Yakima, because, she explained, White Swan is difficult to find. Even with the most detailed directions, I’d still likely get lost, especially because cell service is spotty, rendering Google maps useless. So, we met at the mall in Yakima and drove together.

We wound our way through the country roads along the plateaus and hills north of Yakima. White Swan is a town on the Yakama Reservation. Jenny Tenney teaches math at White Swan High School, which is a public school. The student population is roughly 60% Native, 38% Hispanic, with the remaining 2% a smattering of white and other ethnicities. If they are not at 100%, they are very close in the number of students receiving free or reduced lunch and breakfast. Jenny had already shared this data with me, so I expected to see struggle, but I was not prepared for the reality that hit me once the town came into view (Atlantic article on Native property rights).

White Swan has a population of fewer than 1,000 residents. Housing is limited, and the housing that is available is virtually uninhabitable (Forbes article on government impacts on Native American poverty). This impacts the district’s ability to attract teachers, as there is no housing for them. The school is clearly the pride of the community and well maintained, but is surrounded by shuddered businesses and homes in major disrepair, the majority of which have more than one window covered with particle board. The town suffered a fire in 2011, destroying at least 20 residences. They received FEMA housing, which are still in use today. Many of the burned houses stand, blackened skeletons, a reminder of the fire and the fact that most inhabitants are still unable to rebuild.

Across the street from the school is a burned out, crumbling former business, covered in graffiti. The town library is a small house, surrounded by a chain link fence with barbed wire at the top, clearly aimed at keeping people out. It’s not very inviting. This is what the students in White Swan see every day on their way to school and through the windows as they are trying to learn.

After driving through town, we parked at the school and made our way inside. Like the town public library, White Swan High School is also surrounded by a chain link fence and is padlocked, minus the barbed wire, even during school hours. With a California style campus and several exterior doors, the fence provides at least a sense of security. Despite the chain link, when we entered the school, we entered a different world from the one outside the campus. The hallways are vibrant red and blue. There are pictures of every graduating class on the walls, and trophy cases filled with awards. Native art adorns the walls inside and out and the flag of the Yakama Nation stands alongside the Washington state and US flags. It is clear the school is the pride of the community.

We visited Jenny’s Algebra class. Jenney maintains high expectations of her students and teaches them that “mistakes are expected, respected, and inspected.” Mistakes are how we learn. Her substitute teacher on this day is a graduate from White Swan. She hopes to become a full time teacher. She already has a wonderful rapport with the students, as she has relationships with their families, being a member of the community and a graduate. She is an example for them, their potential made real as one of their instructors. Each classroom is covered in graduation pictures with notes to students’ favorite teachers. Whatever is happening outside of these walls, inside they are students with potential and dreams for their futures.

Jenny took me on a tour of the whole school then drove me along the bus route, so I could see the entire district. We then went to Harrah, a town not far from White Swan, to visit the elementary school. The view from the school is similar to what we saw surrounding the high school, more boarded up houses, and shuttered businesses, although it does seem to be faring a bit better. The elementary school, as well, is surrounded by a fence, but here a security guard opens the fence for us and walks us to the door. The inside is bright and inviting, the walls covered with the faces and work of the students. The classrooms are full of promise and expectation.

My favorite stop is Rainbow’s classroom. He teaches the Native language, Sahaptin, to 3rd and 4th graders. His energy is inspiring. He shows me around his classroom with such pride, explaining his learning objectives for the course and the various visuals that hung around the room to support student learning. Jenny and Rainbow discuss the possibility of him moving to the high school to teach Sahaptin to the upper levels, where it would not count for a language credit, but as an elective (I plan to address this in another post). While he is tempted, he doesn’t want to lose the chance to instill Sahaptin in the younger generation. His hope is that with early introduction, the language will be preserved and used amongst the tribe and down the line there will be more members of the tribe able and willing to teach Sahaptin, an vital part of their culture.

I am forever changed after my visit to White Swan. I thought I understood poverty. I volunteered for the Peace Corps and lived in a developing nation for two years. I lived in one of the poorer boroughs in New York City and taught in another. I’ve seen poverty, but I wasn’t prepared for what I encountered in White Swan right here in Washington State. I am forced to question my own complicity in allowing such poverty to exist when I know we have enough to provide for every person in our nation.

We make many assumptions about people in poverty. We assume so much about them as individuals, but if you really look, you see how hard they are working to survive and to have pride. One home on our route between White Swan and Harrah, was dilapidated and the siding was falling off, but the roof was new and beautiful. The people living there are doing their best with what they have. We must, as compassionate people, venture out and truly see the communities in our state. It is only awareness that will compel us into action. Take a drive this weekend. See how others live. Think about what we can do to ensure every human being has what they need to live and to prosper.

See my interview with Jenny Tenney on teaching here.

Classroom Visits – Witnessing Greatness

On March 8th, I headed to the very small town of Darrington to visit Lynne Clarke, the 2018 Regional Teacher of the Year for the northwest part of our state in education service district 189. Darrington is a logging town of roughly 1400 residents. The 2014 mudslide in Oso, a town just south of Darrington, had and still has a deep impact on the community, who lost friends and family in the slide. They are still recovering from the tragedy. Darrington is tight-knit and Lynne, with her electric personality, is a jewel in their community.

In Darrington all three school levels are together on one campus, with the Middle and High Schools in one building, and the Elementary in a separate building, but still very close by. The staff is more like a family than colleagues, and most wear several hats, and Lynne is no exception. Lynne teaches 9th and 11th grade English, and drama class. She only recently stepped down as the girl’s volleyball coach. She serves on several committees, and works hard to support her students and her colleagues. It’s not the many roles she plays that sets her a part, though. It is her magnetic personality, her love of her students, and her energy and enthusiasm when she teaches. She loves her subject and gets her students to love what they are learning, too.

After being the mystery reader in a second grade class – I read Dr. Seuss’s “Mr. Brown Can Moo, Can You?” (It was so much fun!) – I got to visit with Lynne’s classes. The students asked me questions and we talked about being kind and seeking experiences which challenge our perceptions and getting to know those who are different from ourselves. The students were engaged in the discussion and very curious. This is in no small part because of Lynne and the influence she has on her students. In her classroom, Lynne has created an environment which encourages students to explore who they are, to be curious about the world outside of Darrington, and to be brave in finding new adventures near and far.

The absolute best part of being in Lynne’s class, though, was watching her teach. She is a literal ball of energy and she has a way of getting her students excited about what they are studying. I have rarely seen students get upset when another classmate tells too much about the upcoming events of the novel they are reading, because “I’m not there yet!” and they want to find out what happens by reading it on their own. It is not often that students are engaged in assigned reading.

Lynne explains to her students that “we learn in the place between where we screw up and where we screw up worse.” She does not fear making mistakes in front of her students or making a fool of herself. Being vulnerable and showing her students who she is as a teacher and as a human is part of her magic. She models for students what it means to be real and thus creates space for them to be vulnerable, be foolish, and make mistakes. She is exactly what the students in the very small town of Darrington need.

Just before my visit to Lynne, I visited a teacher some of my readers may recognize, Barbara Tibbits. She is a master teacher in Bothell at Cedar Wood Elementary, where she teaches 4th grade. She is also a Jump Start trainer, plans and runs Homestretch, and is a cohort facilitator for National Board Candidates. In other words, she is a leader in our profession through supporting fellow educators in demonstrating accomplished teaching. When I first arrived in Barbara’s classroom, the students were in book club groups, leading their own learning. Each group chose their own book and were discussing what they had read and the themes of their books. Around the room hung posters, created by each group, about their books. All students were immersed in the work and engaged in learning. This was not a traditional classroom.

I spent the remainder of that day, touring the school, and soaking in the work being done in Barbara’s classroom. After the lunch hour, Barbara called on me to workshop Advocacy with the students. They were writing persuasive letters to policy/decision-makers on topics about which they felt quite passionate. Some wrote to the principal and others to state and federal politicians, including the President. We talked about the power of story and then students brainstormed the stories they could tell that would persuade decision-makers to address their issues. I was impressed with the depth of thought these 4th graders had put into their projects, addressing the homeless, climate-change, eating healthy, and college tuition. I also met with the 5th grade student body president about her proposal to start a book club at school to help struggling readers and to also create space for reading lovers, like herself. She was articulate and passionate and after our meeting she had a solid plan for moving forward. Seeing students take control of their learning, develop their voices, and become empowered to take action, was so cool. At the center of it all, is Barbara. She knows her students, she puts them first in her practice, and it shows in how independent and empowered her students have become.

The biggest benefit of being selected as the Washington State Teacher of the Year is visiting schools across our state. It is an experience that is both awe-inspiring and validating, because I am reminded that the work we do in my school is impacting students, and also that work is being done in every school which places students directly in the center. Many will argue that our system struggles to meet the needs of every student and I agree with that statement, but the absolute truth is much more nuanced. Yes, the system often hinders an educator’s ability to truly meet the needs of every student in their classrooms. However, individual teachers in every school, and, yes, I mean every school, know their students, love their students, and strive to build their practice around the needs of the students in their classroom, and it’s working. We often focus on those schools or classrooms that aren’t working, but my travels have shown me that we should instead focus on what’s working, and give those educators an opportunity to lead from their classrooms and support other educators in also putting students at the center of their practice.

See my interview with Lynne Clarke on teaching here.

A Community of Peers

Melissa Charette (Regional Teacher of the Year for the Olympia area) has created an environment unlike any other I’ve seen in a middle school, ever. I walked in early in the morning, after students were already settled into their first period classes. The hallways were quiet and I could hear the sounds of learning and engagement all around me. Washington Middle School is already a pleasant place to be, with bright hallways, and student artwork on the walls, but Melissa’s class makes it a truly amazing community.

Melissa teaches in a Designed Instruction Special Education classroom. Traditionally, that means students work with their classroom teacher, as well as, one-to-one with Paraeducators, who help them work through lessons and activities specifically designed for them, based on their cognitive and physical abilities. The difference in Melissa’s classroom is that learning happens, not only with instructors, but side-by-side with their mainstream peers. It is a wonder to behold.

When I first walked into her classroom, the room was bustling with activity. Special education students sat with one of their peers working through a variety of activities, from sorting items to reading instruction to counting items and categorizing them. The partnerships were fantastic to witness. In each pair, both students were engaged 100% with the activity and with one another.

As I watched, Melissa told me about several of the students in the room. Two stories stood out. One boy with autism, struggled to acclimate to middle school. He is nonverbal, so communication was difficult at first. He did not know how to communicate with his new teachers and his teachers did not yet know how to communicate with him. His story is amazing, in that he is so completely engaged now, after two years with Melissa, and because of the peer mentor program she has built. This student, who struggles still with communication and with social skills, works with his peer mentor and has developed friendships with his mainstream classmates. The peer mentor program helped this boy with autism find a safe place and new friends.

The second story is about one of the peer mentors. This student, tall for his age and a bit gangly, came in ready to work at the start of his period. He asked a couple of questions then went right to work with his special education peer. He was very engaged with the work and really seemed to enjoy himself as he helped his friend through his work for that period. I asked about the student and Melissa explained that he struggled with behavior and was often in trouble. Melissa heard about him and encouraged him to become a peer mentor for her special education classroom. After becoming a mentor, his behavior completely turned around. The peer mentor program gave him confidence, purpose, and he is more connected with his school.

My favorite part of the day was “Go Noodle.” During “Go Noodle” the entire class, peer mentors, and Paraeducators included, view a web program for getting kids moving and dance along to the silly songs. The characters and songs are wacky and the movements are even wackier and the kids love it. I loved it, too, and quietly schemed on ways I could get my high schoolers to do “Go Noodle.” Mostly, though, I marveled at this awesome community Melissa has built in her classroom.

Melissa’s peer mentor program is a model for the rest of us. In a time when school safety is a constant worry, connections are key. This classroom shows us the importance of helping our students build relationships across difference. As Melissa took me on a tour of the school, every ten feet or so, posters hung on the wall of Melissa’s students and their peer mentors. The peer mentors made the posters to introduce the students to the rest of the school. The faces of the students in the pictures say it all. Both of them have beaming smiles. Their connection is clear. They are not simply mentor and mentee, they are friends.

To learn more about implementing the peer mentor program in your school, check out Melissa’s blog. Also, check out my conversation with Melissa and hear about her experiences as an educator and her messages to other educators, students, and the community.

My Support System

I’m flying home from Washington, D.C., after spending the last three days there for a Teacher of the Year event. This is the second leg of a three-leg flight and this particular part is extra long for state-to-state flying at 3 hours and 47 minutes. Gives me uninterrupted time to think and work, unlike when I drive. I spent the first leg of the flight writing thank you notes to the various presenters and supporters at the National State Teacher of the Year Induction I attended at Google in Mountain View, California, at the beginning of this month.

As I sat in my seat, writing 26 thank you notes, recalling how much I learned and experienced, my hand aching from not being used to writing things by hand, it occurred to me that since being selected as the Washington State Teacher of the Year, I’ve spent on average three nights a week at home and the rest traveling. While it’s been an honor to represent my students, colleagues, and state, and rewarding both personally and professionally, being away from home is rough. I miss my family.

So, when I was writing those thank you notes, I realized I was spending hours thanking virtual strangers, when I should be thanking my amazing family, particularly my husband, Ryan. When he and I met nine years ago, I’m not sure either of us really knew what we were signing up for. He knew I loved adventure, and I knew he’d lived in the same place for his entire life. We were in for quite a journey together.

From the very beginning, Ryan was my champion, even when my many endeavors inconvenienced our life together. You see, I have a bit of a problem with timing. I completed my masters thesis while caring for our brand new baby boy in 2012. I signed up to pursue National Board Certification the year we were selling our house and moving to Spokane. And, I often mess up spring break to attend the Washington Education Association Representative Assembly. Nevertheless, Ryan supports me through it all. He loves me in spite of and because of my passion.

From the very beginning, Ryan was my champion, even when my many endeavors inconvenienced our life together. You see, I have a bit of a problem with timing. I completed my masters thesis while caring for our brand new baby boy in 2012. I signed up to pursue National Board Certification the year we were selling our house and moving to Spokane. And, I often mess up spring break to attend the Washington Education Association Representative Assembly. Nevertheless, Ryan supports me through it all. He loves me in spite of and because of my passion.

This, though, being Teacher of the Year, has kept me away from home far longer than anything in the past and we’ve completely rearranged our lives for it. The entire family, my mom included, has pitched in to make it all work. Still, I am away from home often.

Most recently, as a finalist for National Teacher of the Year, I had to prepare for the selection, which included a keynote speech. I fretted over what I would say, and my husband was there to listen to me. Just days before the selection, I asked if he would watch my speech. He sat down and helped me rearrange, remove, and add elements. He helped me make it into the story I wanted to tell. He did this, knowing that should I be selected, I will be gone even more.

This public acknowledgement of how very much I appreciate my truly amazing husband barely begins to express my feelings. He believes in me and he loves me for everything I am. My trajectory sometimes clashes with what either of us envisioned for our lives together, but through his unending support, we manage to grow together and our relationship grows stronger.

Thank you, Ryan David Brodwater, for believing in me. Thank you for being my champion. Thank you for doing the drop offs, making sure we FaceTime every night when I’m away, grocery shopping, and keeping our family running, all while do amazing things through your own work. But, mostly, thanks for loving me and being proud of me. I couldn’t do any of this without you. Thanks for being my partner through this crazy experience. I love you!

Denisha Saucedo: Making Connections

![]() After yet another school shooting, this one killing 17 of our young people, I already had a post written. I wrote it three months ago after a shooting at an elementary school in California. The week before that, there was a shooting at a church in Texas, and before that the mass murder at a concert in Las Vegas. And, less than a month before that the shooting happened in nearby Rockford, Washington, at Freeman High School. I already wrote about that one, too, for my first post on this site. That in itself is upsetting. In the first four months of my tenure as Teacher of the Year, I’ve already had occasion to write about these atrocities too many times. But, the most upsetting thing is that this keeps happening.

After yet another school shooting, this one killing 17 of our young people, I already had a post written. I wrote it three months ago after a shooting at an elementary school in California. The week before that, there was a shooting at a church in Texas, and before that the mass murder at a concert in Las Vegas. And, less than a month before that the shooting happened in nearby Rockford, Washington, at Freeman High School. I already wrote about that one, too, for my first post on this site. That in itself is upsetting. In the first four months of my tenure as Teacher of the Year, I’ve already had occasion to write about these atrocities too many times. But, the most upsetting thing is that this keeps happening.

We closed 2017 with over 270 mass shootings, many of which occurred at our schools, and we’re working to break that record in 2018. When these horrors happen we focus on the things we think we can change. We want gun laws and regulations (which I agree we need), we want more armed security guards and metal detectors (which I do not agree we need), anything that allows us to believe we can control our environments. Walking through a metal detector is like taking cough syrup. It makes us feel better, but it doesn’t actually solve the problem, it only alleviates the symptoms, while the underlying condition gets worse.

We must look deeper. What makes a person take up arms and turn them on their fellow human beings? It’s disconnection. It’s feeling powerless. This is the root of the problem and much more complicated to fix than installing security devices or keeping our kids inside. It requires time and investment. People feel the most safe when they know they are connected to the people around them, they feel welcome, and they have a sense of empowerment, like they can affect change in their own lives.

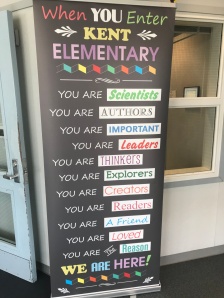

I recently saw this in action in Denisha Saucedo’s classroom at Kent Elementary in Kent, Washington. Ironically, when I first arrived, the class was preparing for a lockdown drill (often referred to as an active shooter drill). I watched Denisha cover the windows and the kids find their places against the wall. The lights were turned off and the doors locked, then everyone was quiet for what felt like an eternity. After the all clear finally came over the loud speaker, class proceeded like any other day. I could dwell on this, the normalcy of lockdown drills. The fact that it’s just another part of students’ days. But, that’s already apparent and been discussed more eloquently elsewhere. Instead, I’ll focus on the community and the connections Denisha builds in her classroom to help her students see their own power, beauty, and potential and that of their classmates.

I recently saw this in action in Denisha Saucedo’s classroom at Kent Elementary in Kent, Washington. Ironically, when I first arrived, the class was preparing for a lockdown drill (often referred to as an active shooter drill). I watched Denisha cover the windows and the kids find their places against the wall. The lights were turned off and the doors locked, then everyone was quiet for what felt like an eternity. After the all clear finally came over the loud speaker, class proceeded like any other day. I could dwell on this, the normalcy of lockdown drills. The fact that it’s just another part of students’ days. But, that’s already apparent and been discussed more eloquently elsewhere. Instead, I’ll focus on the community and the connections Denisha builds in her classroom to help her students see their own power, beauty, and potential and that of their classmates.

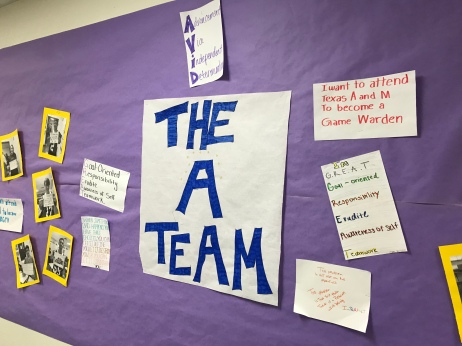

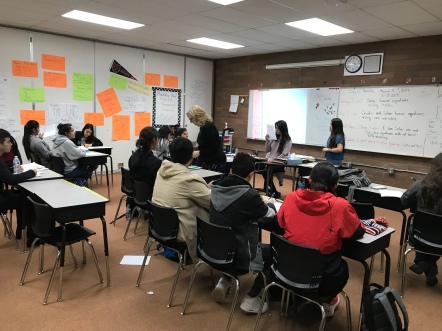

Denisha’s classroom is nothing short of inspiring. Her walls are covered with her students’ goals, both academic and personal, and inspirational messages, telling them that they are the leaders in their own lives. “Make it happen” and “If you believe you can you will!” She explained to me that the students in her class represent a wide range of abilities, but she has them all reading grade-level texts, by providing them appropriate access points, and strategies for comprehension. I see it in action and watch the class navigate a difficult text about California wildfires. Every student is working and engaged, and no student gives up, because they all believe they can do this work. Denisha circulates throughout the room, asking questions and empowering her students to find the answers for themselves. They feel supported, confident, and safe.

Denisha’s classroom is nothing short of inspiring. Her walls are covered with her students’ goals, both academic and personal, and inspirational messages, telling them that they are the leaders in their own lives. “Make it happen” and “If you believe you can you will!” She explained to me that the students in her class represent a wide range of abilities, but she has them all reading grade-level texts, by providing them appropriate access points, and strategies for comprehension. I see it in action and watch the class navigate a difficult text about California wildfires. Every student is working and engaged, and no student gives up, because they all believe they can do this work. Denisha circulates throughout the room, asking questions and empowering her students to find the answers for themselves. They feel supported, confident, and safe.

Later in the day, the STOMP team (Denisha is the advisor/coach) does an impromptu performance for me during their lunch hour. They are a little nervous, but after a couple of minutes they dance and stomp with confidence and excitement, so proud of their choreography and of their team.

After the room cleared, I got to see a bit of Denisha’s magic in connecting with students. A sullen boy had come in and sat at the back table. He was their to refocus after having insulted a classmate in another room. Denisha sat with him and gently helped him articulate what happened. I asked if I should leave the room, that maybe he’d be more comfortable if I wasn’t there. Denisha explained that she didn’t the know the student either and that I should stay, it’s part of the process. Here she was with a boy she didn’t know, building a connection. By the close of lunch, after opening up about what happened, and eating his lunch with an amazing Paraeductor, the student had processed and learned from his mistake, and made two new connections in that classroom.

Denisha Saucedo shows us how to help students feel safe in our schools. She creates an environment in which students feel welcome, and safe, and that they are wanted, that their voices matter, and that they belong. She encourages students to look beyond their own experiences, practice kindness, and get to know one another, to see the value in their classmates. It is only through connections, like Denisha makes with her students, that we will stop wanting to hurt one another. When we recognize that our differences make us interesting and that we all add beauty to the world, that is when our communities and our schools will feel and be safe. Thank you, Denisha, for showing us a safe and empowering classroom.

*See my interview with Denisha to hear about her strengths, lessons learners, and her message to educators, decision-makers, and the community.

Recent Comments