Teaching Fearless

The 2018 Washington State Teacher of the Year's Journey toward Hope

The Poverty Next Door…

Jenny Tenney, the ESD 105 Regional Teacher of the Year, took the day off from school to show me her school district – White Swan. We met in Yakima, because, she explained, White Swan is difficult to find. Even with the most detailed directions, I’d still likely get lost, especially because cell service is spotty, rendering Google maps useless. So, we met at the mall in Yakima and drove together.

We wound our way through the country roads along the plateaus and hills north of Yakima. White Swan is a town on the Yakama Reservation. Jenny Tenney teaches math at White Swan High School, which is a public school. The student population is roughly 60% Native, 38% Hispanic, with the remaining 2% a smattering of white and other ethnicities. If they are not at 100%, they are very close in the number of students receiving free or reduced lunch and breakfast. Jenny had already shared this data with me, so I expected to see struggle, but I was not prepared for the reality that hit me once the town came into view (Atlantic article on Native property rights).

White Swan has a population of fewer than 1,000 residents. Housing is limited, and the housing that is available is virtually uninhabitable (Forbes article on government impacts on Native American poverty). This impacts the district’s ability to attract teachers, as there is no housing for them. The school is clearly the pride of the community and well maintained, but is surrounded by shuddered businesses and homes in major disrepair, the majority of which have more than one window covered with particle board. The town suffered a fire in 2011, destroying at least 20 residences. They received FEMA housing, which are still in use today. Many of the burned houses stand, blackened skeletons, a reminder of the fire and the fact that most inhabitants are still unable to rebuild.

Across the street from the school is a burned out, crumbling former business, covered in graffiti. The town library is a small house, surrounded by a chain link fence with barbed wire at the top, clearly aimed at keeping people out. It’s not very inviting. This is what the students in White Swan see every day on their way to school and through the windows as they are trying to learn.

After driving through town, we parked at the school and made our way inside. Like the town public library, White Swan High School is also surrounded by a chain link fence and is padlocked, minus the barbed wire, even during school hours. With a California style campus and several exterior doors, the fence provides at least a sense of security. Despite the chain link, when we entered the school, we entered a different world from the one outside the campus. The hallways are vibrant red and blue. There are pictures of every graduating class on the walls, and trophy cases filled with awards. Native art adorns the walls inside and out and the flag of the Yakama Nation stands alongside the Washington state and US flags. It is clear the school is the pride of the community.

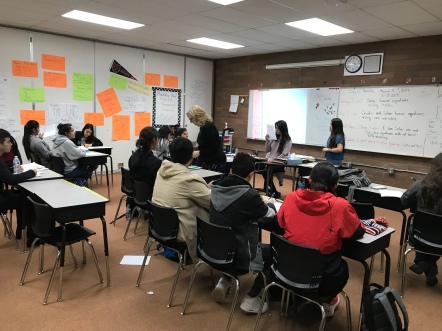

We visited Jenny’s Algebra class. Jenney maintains high expectations of her students and teaches them that “mistakes are expected, respected, and inspected.” Mistakes are how we learn. Her substitute teacher on this day is a graduate from White Swan. She hopes to become a full time teacher. She already has a wonderful rapport with the students, as she has relationships with their families, being a member of the community and a graduate. She is an example for them, their potential made real as one of their instructors. Each classroom is covered in graduation pictures with notes to students’ favorite teachers. Whatever is happening outside of these walls, inside they are students with potential and dreams for their futures.

Jenny took me on a tour of the whole school then drove me along the bus route, so I could see the entire district. We then went to Harrah, a town not far from White Swan, to visit the elementary school. The view from the school is similar to what we saw surrounding the high school, more boarded up houses, and shuttered businesses, although it does seem to be faring a bit better. The elementary school, as well, is surrounded by a fence, but here a security guard opens the fence for us and walks us to the door. The inside is bright and inviting, the walls covered with the faces and work of the students. The classrooms are full of promise and expectation.

My favorite stop is Rainbow’s classroom. He teaches the Native language, Sahaptin, to 3rd and 4th graders. His energy is inspiring. He shows me around his classroom with such pride, explaining his learning objectives for the course and the various visuals that hung around the room to support student learning. Jenny and Rainbow discuss the possibility of him moving to the high school to teach Sahaptin to the upper levels, where it would not count for a language credit, but as an elective (I plan to address this in another post). While he is tempted, he doesn’t want to lose the chance to instill Sahaptin in the younger generation. His hope is that with early introduction, the language will be preserved and used amongst the tribe and down the line there will be more members of the tribe able and willing to teach Sahaptin, an vital part of their culture.

I am forever changed after my visit to White Swan. I thought I understood poverty. I volunteered for the Peace Corps and lived in a developing nation for two years. I lived in one of the poorer boroughs in New York City and taught in another. I’ve seen poverty, but I wasn’t prepared for what I encountered in White Swan right here in Washington State. I am forced to question my own complicity in allowing such poverty to exist when I know we have enough to provide for every person in our nation.

We make many assumptions about people in poverty. We assume so much about them as individuals, but if you really look, you see how hard they are working to survive and to have pride. One home on our route between White Swan and Harrah, was dilapidated and the siding was falling off, but the roof was new and beautiful. The people living there are doing their best with what they have. We must, as compassionate people, venture out and truly see the communities in our state. It is only awareness that will compel us into action. Take a drive this weekend. See how others live. Think about what we can do to ensure every human being has what they need to live and to prosper.

See my interview with Jenny Tenney on teaching here.

Thank you for sharing this experience with others Mandy. I saw a book in a bookstore in Fairhaven yesterday titled, “With Liberty and Justice for Some”. The title has imprinted on my heart and seems fitting for what you saw in White Swan. We have to do better than this.

LikeLike

Thanks, Keyle, I’ll have to read that book. I always knew poverty was an issue, I just didn’t know how very desperate.

LikeLike

I’m trying to find the CBS story on you. . . Please send to me. It was wonderful to hear your story. sdugganpurcell@gmail.com. Thank you for showing what is possible. Susan Purcell

LikeLike

Here is a link: https://www.cbsnews.com/video/meet-mandy-manning-2018-national-teacher-of-the-year/

LikeLike

Pingback: Indigenous Languages are World Languages | Stories From School

Pingback: TEACHER OF THE YEAR – Lexi's Blog